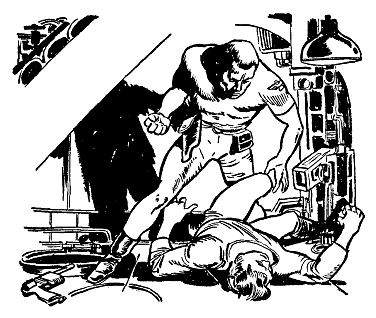

The Set Up: You missed breakfast, overslept, slammed your foot into the coffee table on the way out, ran into stupid drivers on the street, got a flat, got into work late, and were confronted with some serious idiocy by your team. You lost it.

Maybe you're a yeller. Maybe you're a "I'm disappointed in you" type of person. Maybe you're a snarky and sarcastic chainsaw. Whatever your chosen method of taking out your personal unhappiness on other people, you did it today, and it was either not deserved or a serious overreaction.

Having followed my blog this far, one would assume that you don't randomly make people feel bad, as I've pretty much covered how that's counterproductive to managing people. But, as the title of the post states: Screw Ups Happen.

The Affect:

So now you have a team that is literally avoiding eye contact. Some folks are angry at you, either for their own treatment or because they thought your treatment of others was unfair. Others are scared--this is not like you. Their brains will start putting together scenarios you can't even imagine, with the common theme that "something bad" is going to happen to them or the team. Worse, some people are going to internalize your bad morning and think that, even for a brief moment, they are bad people.

Managing This:

This damage is done. There's no going back. Running back to folks and telling them "it's ok" isn't going to cut it. An apology is required; or rather, two. The first is to the people on whom you lost it, in private. No excuses, you should never have talked to them that way, and its all on you. No matter how bad the problem or mistake they ever make, you should never take it out on them like that, and apologize and ask if its possible they accept your apology. Offer them options so that if they can't accept right now, there are things you can do or touch base with them on in the future to try and rectify that trust that you've been building over months but which you just basically took a hacksaw to (my sentence construction here is sucky, I admit that, and I hope you'll accept my apology).

The second apology is to the team. In your next team meeting, which, if it isn't that day, make one that day, call 'em all in and tell them what happened. You can talk about the attack of your killer coffee table and the conspiracy of your alarm clock to prevent your waking, and the overall stupidity of people driving. Make 'em sympathize and, if you can, laugh. Then tell them, soberly, that while those are context for what happened, those are no excuses for what happened today. Then a apologize to the team as whole (not the individuals involved that you already apologized too, as they are likely to feel self-concious or confused if they have already accepted your apology). Tell them they are important to you, and their trust is very important, and that you will work hard not to have a lapse like that again. Explain everyone has lapses, but the trick is not to have too many, and to try never to have the same mistake happen twice (if you can help it). End with the fact that anyone can talk to you at any time about the behavior you express if they are concerned or scared or upset, and that you recommend they wait until you're a little calmer to do it, but that you will not punish anyone for asking you to treat them how they'd like to be treated.

Note, these things will not automatically fix and repair the relationships you thrashed. But it will provide the structure on which new trust can grow and build.

If you find that this is happening more often than random chance would dictate, you might want to talk to someone about your potential anger issues. Anger is a useful emotion--it can get a lot of work done and help you survive some pretty horrible experiences...but those experiences are typically not the kind you find in a healthy work environment. So you need to talk to someone about evaluating both you and what's going on in your life, and your workplace.

In order to provide a safe, trusting place for your team, you need to feel safe and to feel trust as well, and this type of outburst can be a warning sign to which you must pay attention.

Usually, however, these incidents just occasionally happen because you are human. We get aggravated sometimes and behave irrationally. Pick yourself up, dust yourself off, make it as right as you can, and remember it the next time a member of your team goes ballistic for what looks like no reason.